By Rinki Pandey December 26, 2025

“ACH rejection codes” (often called ACH return codes or return reason codes) are the standardized “R-codes” used to explain why an ACH debit or credit failed and was sent back through the ACH Network.

These ACH rejection codes matter because they tell you what went wrong, how quickly you must respond, and whether you can retry the payment, correct details, or investigate authorization and risk.

In real-world payment operations, ACH rejection codes show up everywhere: subscription billing, rent payments, payroll corrections, insurance premiums, loan repayments, and vendor payouts. They also have compliance impact.

Certain codes can indicate unauthorized activity or data quality problems, which can push an originator toward elevated monitoring thresholds.

Many businesses treat ACH rejection codes as “just a declined payment,” but the code is actually a diagnostic label—and reading it correctly is the difference between a fast recovery and repeated failures.

This guide focuses on practical outcomes: what each code means, what usually causes it, what you should do next, and how to reduce repeat returns.

It also includes the complete list of ACH rejection codes (R01–R85) and separates “bank return reason codes,” “ACH operator reject codes,” and special dishonored/contested return situations, because they behave differently.

NACHA maintains and evolves these ACH rejection codes, and industry references note ongoing updates and clarifications (for example, how R11 is used).

What “ACH Rejection Codes” Really Mean (and Why the Terminology Gets Confusing)

People say ACH rejection codes as a catch-all phrase, but in practice it can refer to three different “failure layers”:

- Return Reason Codes (R01–R85): These are the classic ACH rejection codes—an RDFI (the receiver’s bank) sends a return entry back to the ODFI (the originator’s bank). This is the most common “ACH rejected” scenario.

- ACH Operator Reject Codes: These are also “R-codes,” but they happen when the ACH Operator rejects the file/entry due to formatting/field edits or network-level rules. In the EPCOR-style quick reference, these are explicitly labeled “ACH Operator Reject Codes” (examples include R13, R18, R19, R25–R36).

- Dishonored and Contested Dishonored Returns: These are “secondary dispute” processes used when an ODFI dishonors a return (or when an RDFI contests that dishonor). They use codes like R61, R67–R70, and contested codes R71–R77.

Why does this matter? Because the recovery workflow changes depending on which layer you’re dealing with. If you treat an operator rejection like a normal return, you may waste time “contacting the customer” when the real fix is “correct the file format.”

If you treat an unauthorized return like a simple NSF, you risk compliance problems and customer disputes. So, the smartest approach is: use ACH rejection codes as routing rules inside your operations—each code triggers a specific next step.

Modern industry references emphasize that ACH return codes are standardized, maintained by NACHA, and used to communicate failure reasons between institutions.

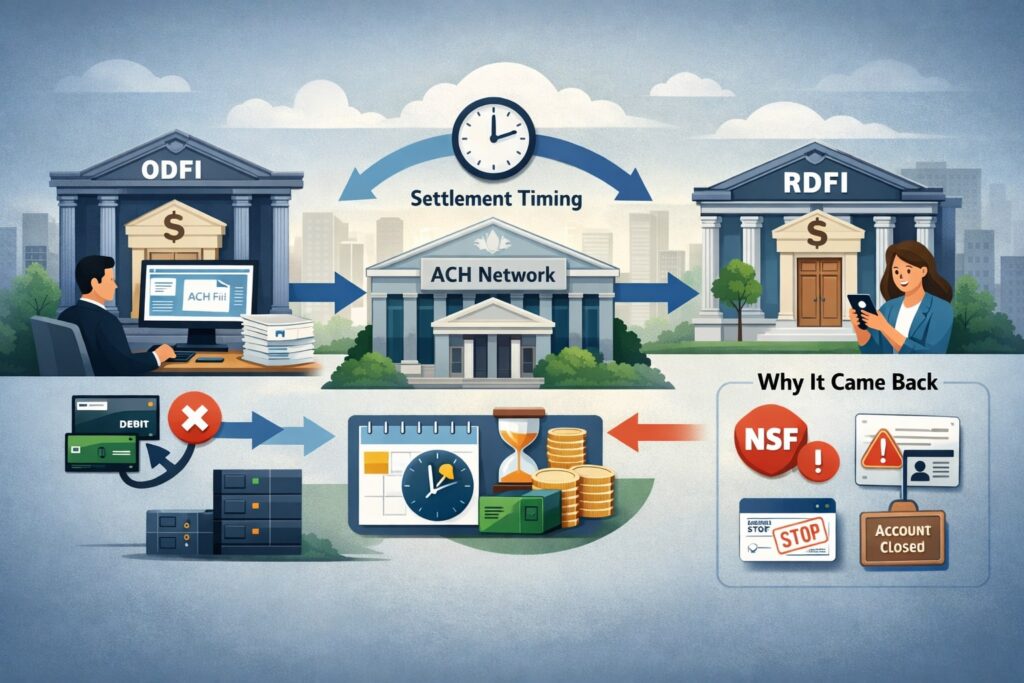

How ACH Returns Happen in Practice (ODFI, RDFI, Settlement Timing, and “Why It Came Back”)

To understand ACH rejection codes, it helps to understand the basic flow:

- The Originator (your business or your customer’s biller) initiates a debit or credit.

- The entry is sent through the ODFI (the originator’s bank or payment provider).

- It passes through an ACH Operator for clearing and settlement.

- The RDFI (the receiver’s bank) posts it to the receiver’s account.

If anything fails—wrong account number, closed account, stop payment, invalid routing edits, authorization dispute—the transaction can be returned or rejected with an ACH rejection code.

The important detail is that ACH is not a “live approval” network like many card transactions. It’s batch-based, so the failure can show up after the entry was transmitted and even after settlement windows start.

That’s why ACH rejection codes are operationally “loud.” A single error can create a loop: the payment fails, the customer service team emails the customer, the billing system retries, and the error repeats. Your goal is to map each ACH rejection code to:

- Root cause (data issue, account status, compliance dispute, formatting)

- Allowed action (retry, correct and resubmit, get new authorization, stop retrying)

- Timing (how quickly returns happen and how long disputes can last)

EPCOR’s 2025 ACH quick reference guide highlights how incorrect use of return reason codes can increase operational risk and emphasizes structured exception handling.

The Complete List of ACH Rejection Codes (R01–R85) With Meaning and Best Next Steps

Below is the complete list of ACH rejection codes used across returns, operator rejects, dishonored returns, contested dishonored returns, and international (IAT) gateway returns.

Where the network has “unused/reserved” numbers or rarely used categories, you’ll see that called out—because a “complete list” should include what people might see in logs, even if it’s uncommon.

Practical tip: In internal tooling, store (code, title, category, retry_allowed, max_retries, require_customer_contact, compliance_flag). Your workflows will get dramatically faster.

Common administrative and funding-related ACH rejection codes (R01–R04, R09, R20)

These are among the most frequent ACH rejection codes because they reflect basic account conditions or input errors.

- R01 — Insufficient Funds: Available balance can’t cover the debit. Next step: notify customer, retry using smart timing (avoid payday+1 assumptions without data), limit retries, and consider alternative rails.

- R02 — Account Closed: The account was closed. Next step: stop retries; obtain new bank details or alternate payment methods.

- R03 — No Account / Unable to Locate Account: Account number structure is valid but doesn’t match an open account. Next step: verify bank details; do not “blind retry.”

- R04 — Invalid Account Number Structure: Fails check digit/format. Next step: correct data at source; add validation rules to onboarding forms.

- R09 — Uncollected Funds: Ledger may show funds but they’re not available (items still collecting). Next step: retry later; message customer about funding timing.

- R20 — Non-Transaction Account: Account type can’t accept these transactions. Next step: update account type or use a different account.

These ACH rejection codes are “administrative” in the sense that they usually don’t imply fraud, but they do imply data quality and cash flow issues.

The best prevention strategy is to combine (1) account validation, (2) customer-friendly messaging, and (3) retry logic that avoids excessive reattempts. Excessive retries can worsen return rates and customer experience.

Authorization, consumer dispute, and stop-payment ACH rejection codes (R05, R07, R08, R10, R11, R29)

These ACH rejection codes can trigger higher risk scrutiny because they involve authorization and disputes.

- R05 — Unauthorized Debit to Consumer Account Using Corporate SEC Code: A corporate-formatted debit hit a consumer account and wasn’t authorized; written statement required in many cases. Next step: compliance review; confirm SEC code usage and authorization method.

- R07 — Authorization Revoked by Customer: The receiver revoked permission; written statement and extended return window are typical. Next step: stop future debits until new authorization is obtained.

- R08 — Payment Stopped: Stop payment placed on the debit. Next step: confirm if it’s one payment or all future payments; stop retries unless you have updated authorization.

- R10 — Customer Advises Originator Not Known / Not Authorized: Indicates the receiver claims the originator is not authorized or not known; a written statement is typically required. Next step: treat as high risk; review authorization trail and customer identity, and do not “autopilot retry.”

- R11 — Customer Advises Entry Not in Accordance With Authorization Terms: Authorization exists, but the amount/date/terms are wrong. Next step: fix billing logic and confirm terms; collect a corrected authorization if needed.

- R29 — Corporate Customer Advises Not Authorized: Non-consumer receiver claims not authorized (corporate accounts). Next step: immediate review; for corporate entries this has strict handling expectations.

Operationally, these ACH rejection codes should trigger a “compliance lane” workflow: preserve authorization evidence, stop further pulls, and communicate clearly.

Industry references also emphasize that NACHA can update code usage and clarifications over time (such as the repurposing/clarifying of R11 described in modern references).

Account status changes and identity/lifecycle ACH rejection codes (R12, R14–R16)

These are less frequent but important because they represent real-world account lifecycle events.

- R12 — Account Sold to Another DFI: The account relationship moved. Next step: obtain updated routing/account details (or bank-provided updated information where available).

- R14 — Representative Payee Deceased or Unable to Continue: Payee status change. Next step: update payee/beneficiary arrangements; coordinate with the receiving institution’s required documentation.

- R15 — Beneficiary or Account Holder Deceased: Next step: stop entries; follow estate/beneficiary procedures and re-credential payments appropriately.

- R16 — Account Frozen / Entry Returned per OFAC Instruction: Account access restricted by legal action or OFAC instruction. Next step: do not retry; escalate to compliance/legal.

These ACH rejection codes often require human handling. Your automation should detect them and avoid retries that will almost certainly fail and can create customer harm.

File edit criteria, duplicates, and credit refusal ACH rejection codes (R17, R23, R24)

These sit between “bank return logic” and “data hygiene.”

- R17 — File Edit Criteria / Suspicious Entry / Improperly-Initiated Reversal: Often used when fields not edited by the operator fail RDFI edits, or when an entry appears questionable. Next step: verify entry legitimacy, confirm account number validity, and validate reversal logic.

- R23 — Credit Declined by Receiver: Receiver refuses a credit under certain conditions (wrong amount, litigation, overpayment, or other refusal reasons). Next step: contact receiver for corrected instructions; avoid resending without confirmation.

- R24 — Duplicate Entry: Appears to duplicate another entry (trace, date, amount). Next step: reconcile internal ledger and ensure you’re not double-sending; confirm reversals vs duplicates.

For billing systems, R24 is a classic sign of idempotency problems. Fixing the root cause (dedupe keys, trace mapping, retry safety) reduces long-term return rates.

Special conversion/check-related ACH rejection codes (R37–R39, R50–R53, R33)

These relate to check conversion or special entry classes (ARC/BOC/POP, RCK, XCK). Even if you don’t originate these often, you can still see the ACH rejection codes in bank reports.

- R33 — Return of XCK Entry: An XCK entry returned at RDFI discretion; can be returned up to 60 days after settlement. Next step: review XCK eligibility and source documentation.

- R37 — Source Document Presented for Payment: The original source document was presented; requires statement and return timing rules. Next step: coordinate to avoid double presentment.

- R38 — Stop Payment on Source Document: Stop payment on the underlying document. Next step: do not retry; resolve with the customer.

- R39 — Improper Source Document: Source document was improper. Next step: investigate document capture/authorization chain.

- R50 — State Law Affecting RCK Acceptance: A legal/state rule impacts RCK acceptance. Next step: route to compliance and adjust entry method.

- R51 — Item Related to RCK Entry Ineligible / RCK Improper: Ineligible item, notice not provided, signature issues, altered item, amount mismatch; written statement required. Next step: treat as high severity, validate RCK eligibility.

- R52 — Stop Payment on Item: Stop payment placed on the related item. Next step: stop and resolve with the customer.

- R53 — Item and RCK Presented for Payment: Both were presented; requires statement and timing rules. Next step: investigate double presentment and correct processes.

These ACH rejection codes are excellent indicators of process gaps in check conversion handling. If you see them frequently, it’s a signal to audit how you obtain notice, capture items, and handle representments.

International (IAT) gateway return ACH rejection codes (R80–R85)

If your entry is IAT or involves gateway processing, these ACH rejection codes appear:

- R80 — IAT Entry Coding Error: Invalid country/currency/qualifiers or other IAT formatting. Next step: validate required IAT fields and your gateway rules.

- R81 — Non-Participant in IAT Program: Gateway doesn’t have agreement to process IAT entries. Next step: confirm gateway capability and configuration.

- R82 — Invalid Foreign Receiving DFI Identification: Foreign receiving identifier invalid. Next step: correct foreign bank reference data.

- R83 — Foreign Receiving DFI Unable to Settle: Foreign settlement issues. Next step: coordinate with gateway/payment provider; retry only if advised.

- R84 — Entry Not Processed by Gateway: Gateway returns at discretion due to risk or foreign system limitations. Next step: re-route payment method or adjust risk/compliance.

- R85 — Incorrectly Coded Outbound International Payment: Identified as outbound international but not coded as IAT SEC code. Next step: correct SEC coding and IAT requirements.

Even if you rarely originate IAT, these ACH rejection codes are “high leverage” because one configuration mistake can cause repeated failures.

ACH Operator Reject Codes (network/file level): R13, R18, R19, R25–R36, and related

When the ACH Operator rejects the entry, you’re dealing with a technical failure, not a customer funding issue.

From the EPCOR quick reference appendix section labeled “ACH Operator Reject Codes,” examples include:

- R13 — Invalid ACH Routing Number (invalid routing/Gateway ID)

- R18 — Improper Effective Entry Date (outside processing window)

- R19 — Amount Field Error (non-numeric, wrong for certain entry types, or exceeds limits for some conversions)

- R25 — Addenda Error

- R26 — Mandatory Field Error

- R27 — Trace Number Error

- R28 — Routing Number Check Digit Error

- R30 — RDFI Not Participant in Check Truncation Program

- R32 — RDFI Non-Settlement

- R34 — Limited Participation DFI

- R35 — Return of Improper Debit Entry

- R36 — Return of Improper Credit Entry

Next steps for operator rejects:

- Stop retries immediately (retries won’t fix formatting).

- Fix the file/field issue (routing edits, effective date windows, addenda formats, transaction code compatibility).

- Add pre-submission validation so the same ACH rejection codes don’t reappear.

Dishonored and Contested Dishonored Return ACH rejection codes (R61–R77)

These ACH rejection codes are used when returns are disputed or mishandled.

- R61 — Misrouted Return: Incorrect routing number placed in the Receiving DFI Identification field. Next step: correct routing and resend properly (within rules).

- R62 — Return of Erroneous or Reversing Debit: Used in limited reversal scenarios; can trigger follow-on disputes.

- R67 — Duplicate Return: ODFI received more than one return for the same entry.

- R68 — Untimely Return: Return not sent within an established timeframe.

- R69 — Field Error(s): Return contains incorrect/incomplete info; the EPCOR guide even lists subcodes for which field is wrong.

- R70 — Permissible Return Not Accepted / Return Not Requested: Used when R31/R06 was not properly requested or accepted.

- R71–R77 — Contested Dishonored Return Codes: Used to contest dishonored returns (misrouted, untimely dishonor, timely original return, corrected return, etc.).

These ACH rejection codes are a sign your operation is in “exception escalation mode.” Most businesses rarely see them unless they’re high volume or have dispute-heavy categories. If you do see them, create a specialized queue handled by payments ops leadership.

“Reserved / Rare / Platform-Specific” code numbers (Why some R-codes look empty)

Many public lists show “N/A” for certain R-code numbers or omit them entirely. Modern references list codes such as R40–R47 (and show N/A in some columns) and show that not every number is used like a common return reason code.

In practice, you should treat “odd” ACH rejection codes in the R40s–R40s range as special or uncommon categories (often tied to enrollment/government enrollment processes). If you see one in production, confirm:

- Which rail or program produced it (ENR/government enrollment-related, operator edits, or a provider-specific mapping),

- Whether your processor is mapping internal reject reasons into “closest ACH rejection code,” and

- Whether the entry class or message type was miscategorized.

How to Use ACH Rejection Codes to Build a High-Performing Recovery System

A list of ACH rejection codes is only useful if it changes what you do next. A high-performing recovery system treats ACH rejection codes as inputs into automation:

1) Categorize every ACH rejection code into one of four lanes

- Lane A — Data Fix Required: R03, R04, many operator rejects (R25–R28).

- Lane B — Retry Eligible: R01, R09 (with guardrails).

- Lane C — Customer Action Required: R02, R12, R20, R23.

- Lane D — Compliance / Dispute: R05, R07, R10, R11, R16, R29.

EPCOR’s guide frames exception handling as a risk and process discipline issue—exactly why “lane routing” reduces operational risk.

2) Add “retry intelligence,” not “retry spam”

For retry-eligible ACH rejection codes, aim for fewer, smarter retries:

- Use “payday-aware” timing only if you have customer-level behavioral data.

- Cap retries, and stops if a different code appears (e.g., R01 becomes R02).

- Message customers proactively with a one-click update path for bank details.

3) Track “return patterns,” not only “return volume”

A single ACH rejection code can be a symptom of upstream issues:

- Many R04 → poor input validation or bad bank detail capture

- Many R10/R11 → unclear authorization language or billing logic errors

- Many R24 → duplicate sending/idempotency failures

Compliance and Risk Signals Hidden Inside ACH Rejection Codes

ACH rejection codes do more than explain a failure—they influence risk scoring by banks and providers. Unauthorized-type ACH rejection codes (R05, R07, R10, R11, R29) should trigger:

- Preservation of authorization records,

- Customer identity verification checks,

- Review of SEC code appropriateness,

- Review of marketing disclosures and consent UX.

Operational references note that return reason codes are governed by NACHA rules and have prescribed handling.

For businesses, the safest approach is to treat certain ACH rejection codes as “do not retry without investigation.” Retrying an unauthorized return can escalate complaints, increase dispute rates, and harm your acceptance with partners.

Future Outlook: Where ACH Rejection Codes and Return Handling Are Heading

Over the next few years, expect ACH rejection codes to become even more operationally important, not less. Three trends push in that direction:

- More automation, more volume, more scrutiny: As ACH continues scaling, exception handling becomes a bigger lever. Automated recovery systems will increasingly use ACH rejection codes as rule triggers, not just reporting fields.

- Faster settlement expectations: Same-day processing and faster posting behaviors raise customer expectations. When customers expect “near instant,” even normal ACH rejection codes feel like a major disruption—so merchants will invest more in prevention and real-time validation.

- Ongoing rule clarifications: Industry references emphasize that ACH return codes evolve and NACHA clarifies and updates codes (including how certain codes like R11 are used).

A practical “future-proof” move: build your system so new or clarified ACH rejection codes can be added without engineering downtime (configuration-driven code tables, versioned policies, and audit logs).

FAQs

Q.1: What is the difference between ACH rejection codes and ACH return codes?

Answer: “ACH rejection codes” is a common phrase people use, but the network-standard term is usually ACH return codes or return reason codes. Some “rejections” are actually ACH Operator rejects, which are file/network-level issues. EPCOR-style references separate “Return Reason Codes” from “ACH Operator Reject Codes.”

Q.2: Are there really 85 ACH rejection codes?

Answer: Yes—modern industry references commonly describe R01–R85 as the full set, even though many are uncommon or program-specific.

Q.3: Which ACH rejection codes should never be retried automatically?

Answer: As a rule: authorization and compliance-related ACH rejection codes (R05, R07, R10, R11, R16, R29) should not be retried without investigation and customer confirmation. The EPCOR guide descriptions for several of these emphasize written statements, authorization revocation, or restricted accounts.

Q.4: What’s the most common ACH rejection code for billing?

Answer: For recurring debits, R01 (Insufficient Funds) is widely treated as one of the most common. Many businesses build retry logic specifically around R01 and R09.

Q.5: Why do I see an ACH rejection code like R63 or R66 in my reports?

Answer: Those codes are typically tied to error and correction workflows (often in return/dispute contexts) and can appear in some systems depending on how returns and corrections are processed.

If you’re seeing R63 or R66, treat it as a signal to verify the transaction/return details and confirm how your processor maps exceptions. (Examples of R63 and R66 are widely documented in industry references.)

Conclusion

Having the complete list of ACH rejection codes is useful, but the real win is using those ACH rejection codes to run a disciplined operation: reduce preventable failures, recover revenue faster, and lower risk.

The best teams don’t just “note the code”—they route each ACH rejection code into the correct lane (data fix, retry, customer action, or compliance), measure patterns, and improve the upstream funnel so the same ACH rejection codes don’t repeat.

Keep your ACH rejection codes reference updated, because NACHA guidance and interpretations can evolve, and modern references explicitly call out ongoing clarifications (including how certain codes are repurposed or used).

Leave a Reply